It’s official: El Niño is here

5 min read

Australasian climate authority Bureau of Meteorology declared El Niño events were officially underway on 19 September. The declaration was made after three of the four criteria were met, including a sustained response in the atmospheric circulation above the tropical Pacific.

El Niño occurs every two to seven years on average, and episodes typically last nine to 12 months. It’s a naturally occurring climate pattern associated with the warming of the ocean surface temperatures in the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean. This warming alters atmospheric circulation patterns, leading to significant changes in global weather and climate. New Zealand, due to its location in the Pacific, experiences both direct and indirect effects of El Niño.

While El Niño was first publicly discussed by forecasters more than a year ago, saying it was likely to come in around winter or early spring in 2023, the World Meteorological Organization first declared the onset of El Niño conditions in July.

“El Niño conditions have developed in the tropical Pacific for the first time in seven years, setting the stage for a likely surge in global temperatures and disruptive weather and climate patterns,” said WMO secretary-general prof. Petteri Taalas.

“The onset of El Niño will greatly increase the likelihood of breaking temperature records and triggering more extreme heat in many parts of the world and in the ocean.”

According to the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA), El Niño Alert criteria continued to be met during August.

It said abnormally warm waters are predicted to surface and expand westward over the course of the next six months, culminating in a strong or very strong El Niño event that “rivals records”.

NIWA meteorologist Tristan Meyers said this summer season is looking to be Aotearoa’s hottest ever.

“This year’s El Niño is no wee lad, more a monster bad boy, and will be the strongest in 80 years,” he said.

“Indicators do point to El Niño. We also look at another climate driver, the Indian Ocean Dipole. The combination of the two causes warm temperatures that we’re already seeing. Going into summer we could see more records in the high 30˚Cs.”

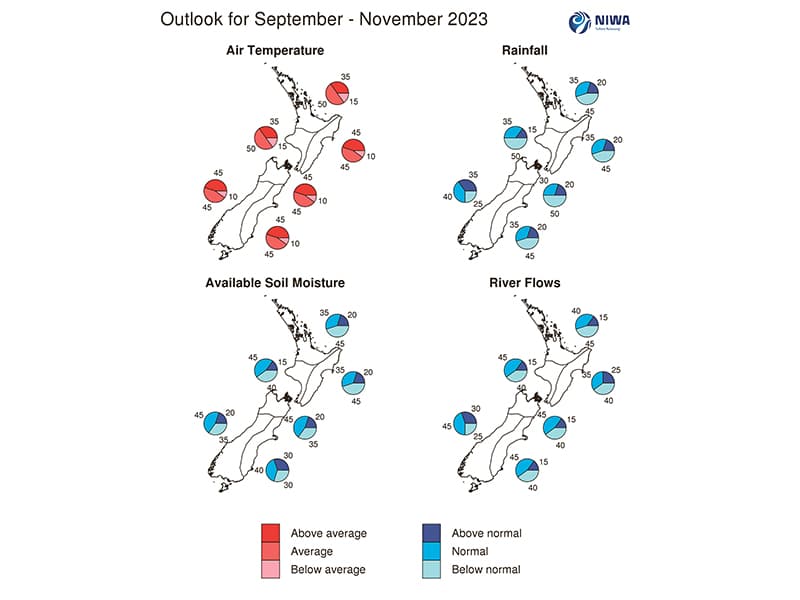

What to expect

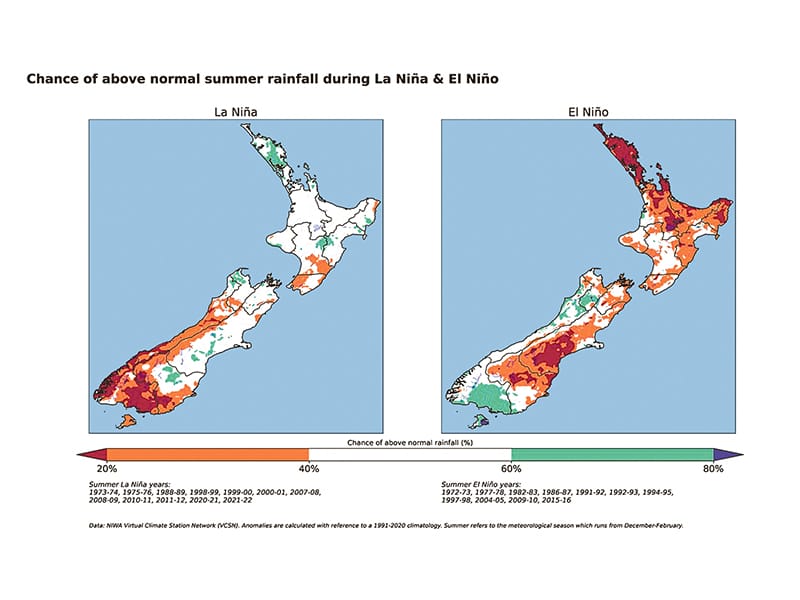

In general, an El Niño year can bring stronger or more frequent winds from the west in summer, south-westerlies in spring and autumn, cooler land and sea temperatures, more rain in the west and less in the east, and a higher chance of cyclones in New Zealand and the Pacific Islands. El Niño events increase the risk of extreme temperature shifts, such as heatwaves and hotter days.

According to Weatherwatch.co.nz, El Niño conditions are going to continue to set in and expand for the rest of 2023. This means summer and 2024 will kick off at the peak of the weather event. It may not be until later in autumn or even winter of 2024 before it fades.

“El Niño and spring are similar in nature – i.e., lots of windy westerlies,” Weatherwatch’s Phil Duncan said. “But this summer may well see westerlies blowing off and on, helping scorch eastern and inland parts of New Zealand. More high pressure may also bring calm spells – but longer dry spells.”

Impact on weather patterns

El Niño has far-reaching effects on weather patterns and ecosystems. It can disrupt traditional weather patterns, influence ocean currents, and affect marine life and the fishing industries.

During an El Niño event, New Zealand tends to experience altered weather patterns. The warming of the Pacific Ocean affects the positioning of the jet stream, a fast-flowing ribbon of air in the atmosphere. This can result in altered wind and rainfall patterns across the country.

One of the most significant impacts is a shift towards drier conditions in the eastern parts of both the North and South Islands. Regions that typically receive substantial rainfall may experience reduced precipitation, leading to drought-like conditions. Some areas on the western sides of the islands may experience increased rainfall and flooding.

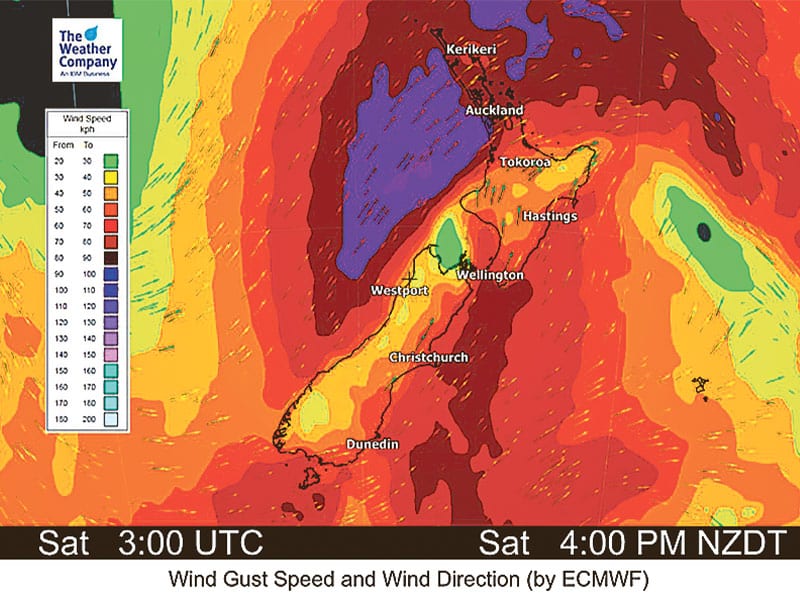

New Zealand may experience stronger westerly winds during El Niño, potentially leading to rougher seas and challenging conditions for recreational boaters. These intensified winds can pose significant challenges, making navigation and control of boats more difficult.

Impact on sea temperatures

El Niño events cause notable changes in sea surface temperatures. The warming of the Pacific Ocean leads to higher sea surface temperatures in the Tasman Sea. These elevated temperatures can disrupt marine ecosystems and have a profound effect on marine life.

Warmer sea surface temperatures may cause shifts in the distribution and abundance of marine species. Some species may migrate to find more suitable temperature ranges, impacting local fisheries. Changes in ocean temperatures and altered ocean currents can disrupt the usual distribution and behaviour of fish stocks. Some species may move to deeper or cooler waters, making them more challenging for anglers to access. Fisheries that heavily rely on certain species may experience reduced catches during El Niño events, affecting both commercial and recreational fishing activities.

Due to altered migration patterns, changes in feeding behaviour and shifts in fish distribution, anglers often experience reduced catch rates and smaller catch sizes during El Niño events.

Marine heatwaves also adversely affect marine life, increase rain and tropical cyclones, and may lure sharks. In Hawaii, international surfer Mark Healy said he had never seen so many aggressive sharks around Oahu, suggesting a transition into an El Niño.

“I’ve never lost fish to sharks around Oahu off my spear and I got taxed three days in a row on three different sides of the island,” he said.

Adapting to El Niño

To mitigate the impacts of El Niño on marine ecosystems and the fishing industry, proactive measures are necessary. Enhanced monitoring and early warning systems can help fishing communities prepare for potential disruptions caused by changing ocean conditions. Timely and accurate information about ocean temperatures, currents, and potential shifts in fish distribution can aid in making informed decisions about fishing operations.

Additionally, diversifying fishing practices and exploring alternative fisheries that are less affected by El Niño events can help reduce vulnerability.

Proactive monitoring, adaptation, and sustainable fishing practices are essential to mitigate the impacts and ensure the resilience of the marine and fishing sectors in New Zealand amidst these climatic changes.

Safety concerns for recreational boaters

Rough seas and dangerous swells: Stronger winds and altered weather patterns during El Niño can result in rough seas and dangerous swells, posing a significant risk to recreational boaters. Boaters need to exercise caution, potentially reconsidering their plans and routes to ensure safety on the water.

Unpredictable weather changes: The rapid and sometimes unpredictable changes in weather during El Niño can catch boaters off guard. It’s vital for boaters to stay informed about weather forecasts, be prepared for sudden changes, and always prioritise safety by having appropriate safety gear onboard.

Limited access to waterways: The reduced water levels caused by drought during El Niño events can limit access to waterways. Boaters must plan their trips carefully, considering the availability of navigable waters and adjusting their itineraries accordingly to ensure a safe and enjoyable boating experience.